Niagara has five major waterways that are large enough to carve the region up and define its boundaries: Twelve Mile Creek, the Welland River, the Welland Canal, the Chippawa-Queenston Power Canal and the Niagara River. Access through riverine systems is a component of making high-quality metroscapes, but larger systems like this deserve more detailed scrutiny.

Overall, public access to the riverbank is alright on a reach basis. Over 75% of all five systems are accessible from at least one side. Most of the remaining restricted reaches have at least one bank that is publicly-owned with restricted access (a condition usually easier to change than private property).

When characterizing the ownership at the banks, the Welland River greatly skews the overall picture due to its largely rural nature, and significant private encroachment within its lower urban reaches. So ignoring it, only 7.1% of the riverbanks on the other systems are privately owned and inaccessible. Over 60% of them are publicly accessible, and the remaining third are publicly owned and restricted.

There’s quite a range of different land use categories up and down the sum of the five systems, 15 categories in total. That masks the characteristic differences between them, with a couple only having 5 or 6 categories to break them down.

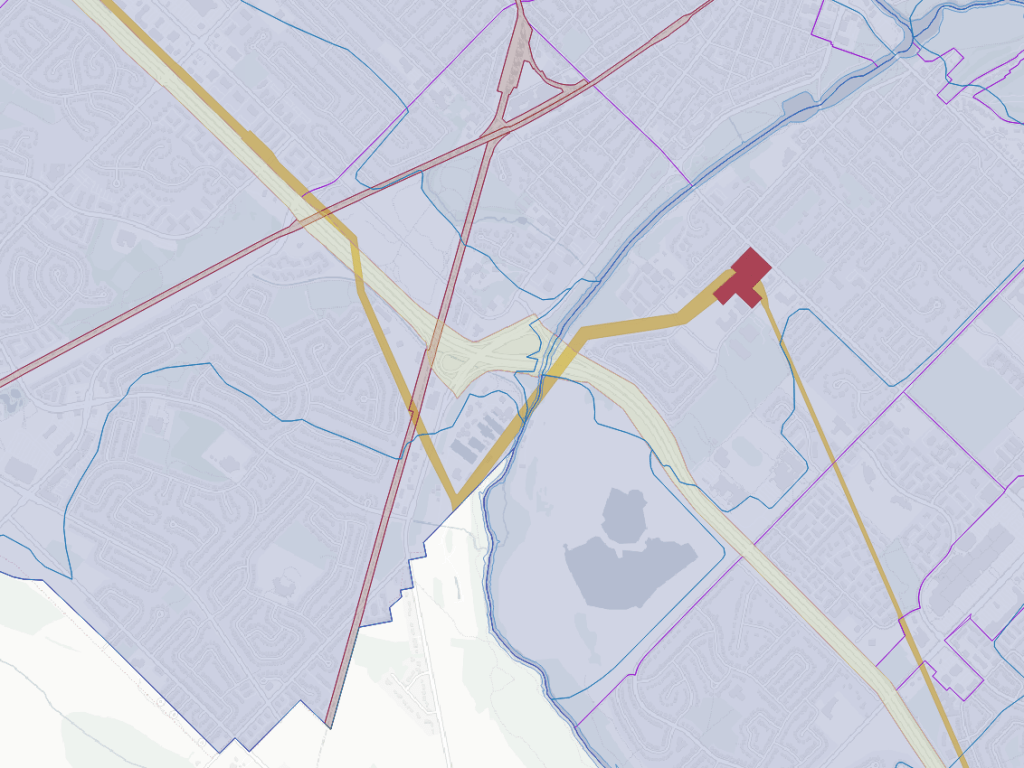

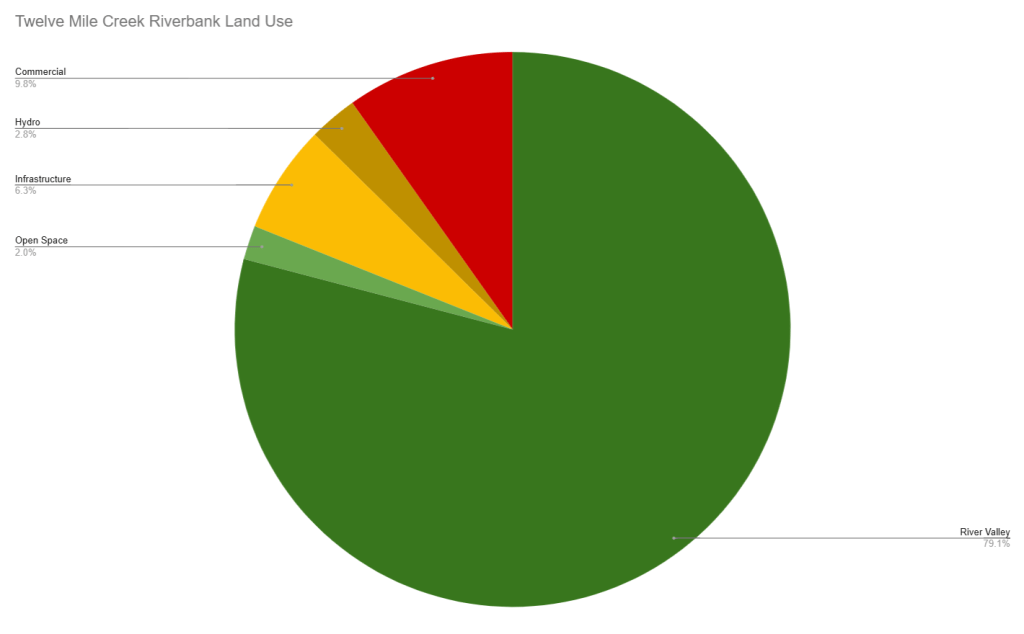

Welland Canal System

The Welland Canal System (which includes the currently operational Fourth Canal, Recreation Canal and southern First Canal) is an interconnected channel system that dates back to 1883, with a huge upgrade in 1932 and a significant change as recently as 1973 (with the diversion around Welland).

The Welland Canal System holds a lot of promise. Over 59.7% of it is already public, and it’s only another 8% that’s private. The remaining third is already in public hands, and is restricted for what I suspect would be labelled as ship safety and infrastructure integrity. I’m not keen that it’s unmitigable.

This is a huge opportunity for the federal government to issue a few directives to make a huge local improvement for only a little capital cost. For example, does a coast guard need to be completely isolated within 4 kilometres of shoreline and bank, as well as 17 hectares of woodlands? Or can we relax that a bit? Overall, huge opportunity exists to open up access to the remaining passive lands.

There’s also opportunity to be bold, and enhance the perimeter of active lock and dock areas, even if it does not “provide direct public access”. A good example of this is the success of the Lock 7 viewing area. People still love watching huge unique infrastructure; why not show off this Canadian portion of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway that is still important for Great Lakes economies.

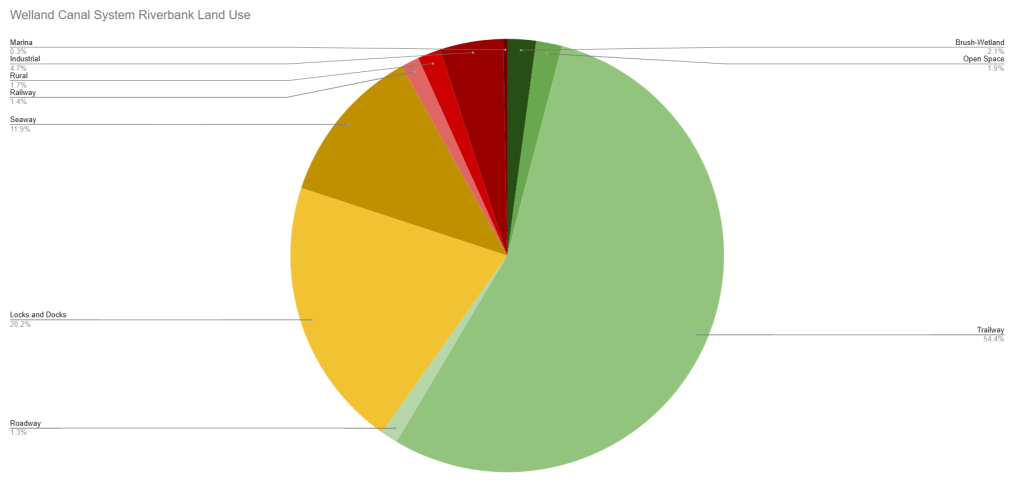

Twelve Mile Creek

Twelve Mile Creek is not as it was. It was part of the Welland Canal System until the Third Welland Canal was completed in 1887. Even then, it’s mouth was still used by the Third Welland Canal (albeit now Martindale Pond after being dammed up) until the last one opened in 1932. But modification of this creek continued as canal water continued to be dumped into the system through DeCew Falls Hydro Generating Station 2 in 1943.

This is a system that I have low hopes for changing anytime soon. The nearly 10% of commercial banks are actually tableland plazas with wetlands down below, neither of which are conducive for reconfiguration. DeCew Falls Hydro Generation Station and Highway 406 are a bit insurmountable as well, but could benefit from better links between the banks to help bridge the gap.

That just leaves Welland Vale Island, which is the one smaller reach that could benefit from a major gap filling. Right now, there’s such a devastating dead-end at the back end of Biolyse Pharma. It would at least be nice to revive the diversion channel and flank it with a shorter detour.

Welland River

The Welland River is the one system that throws off the averages. A part of that stems from over half of the river being rural, between the Welland Bypass Canal and Lyon’s Creek. Another part of it is a function of the unclear property rights in the community of Chippawa (which was amalgamated into the City of Niagara Falls in 1970). And perhaps that stems from the management of the part of the river that feeds the Beck Hydroelectric Generation Stations; during certain times, the flow of the river is reversed to go westerly from the Niagara River to the Chippawa-Queenston Power Canal.

Over 55% of the Welland River’s banks is private property. One quarter is simply classified as rural land between Welland Island and the village of Chippawa, which may change as development spreads between Niagara Falls and Thorold. One fifth is still private residences occupying the banks in built-up areas.

While I have categorized many stretches as “private property”, I have further broken this down in the metadata to capture a number of strange stretches in the Chippawa neighbourhood. The land is manicured grass, and the parcel geometry suggests it is open space held by Ontario Power Generation, but it’s occupied on the edge by private docks. I’m not sure what the exact property rights are through these stretches, but if the public is entitled to enjoy some of the space, that’s not clearly defined. I am labelling it as private lands until I can get more clarity.

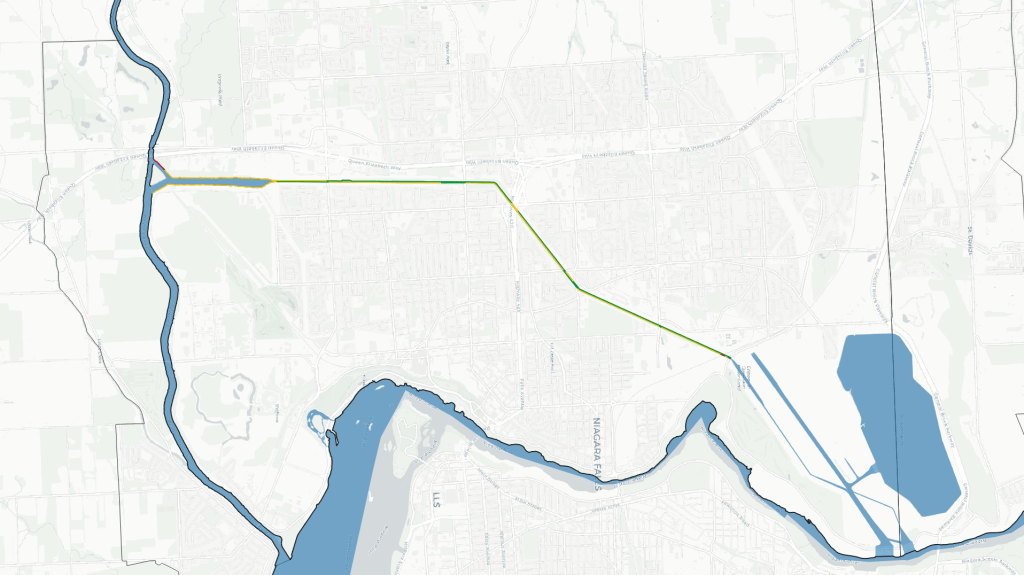

Chippawa-Queenston Power Canal

This may be called a canal, but it is far from a boring thing. This is a deep cut into Niagara’s geology formed over a century ago, and has in some sense been maintained in a wild state outside of the main flow area.

This is clearly reflected in the bank use. Only a smidge is considered occupied (to a degree) by commercial land, with the southwest corner flanked by Jellystone Park and one northeast bit where it’s blocked by a Canadian National railway bridge. Over half of the rest that isn’t open to the public is simply blocked off by Ontario Power Generation as a dangerous hydroelectric area.

There have been recent improvements however. The Millennium Recreational Trail is the primary trail following the canal, accounting for 40% of the banks of the canal. While it’s still set far away from the canal and heavily fenced due to the deadly risks of falling in, it still opens it up in spirit and offers great neighbourhood connections. It was constructed over the past 25 years, with the most recent link between Dorchester and McLeod Roads being completed in 2022. The City considers this “complete”, but I think there’s plenty of opportunity to double it up, make new mid-block crossings, and bridge the gap at Highway 420.

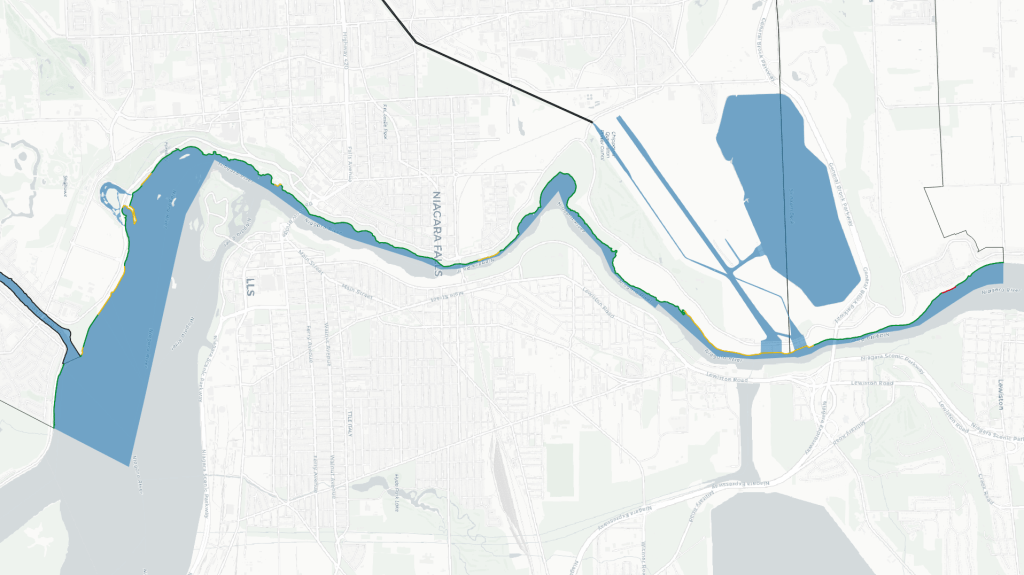

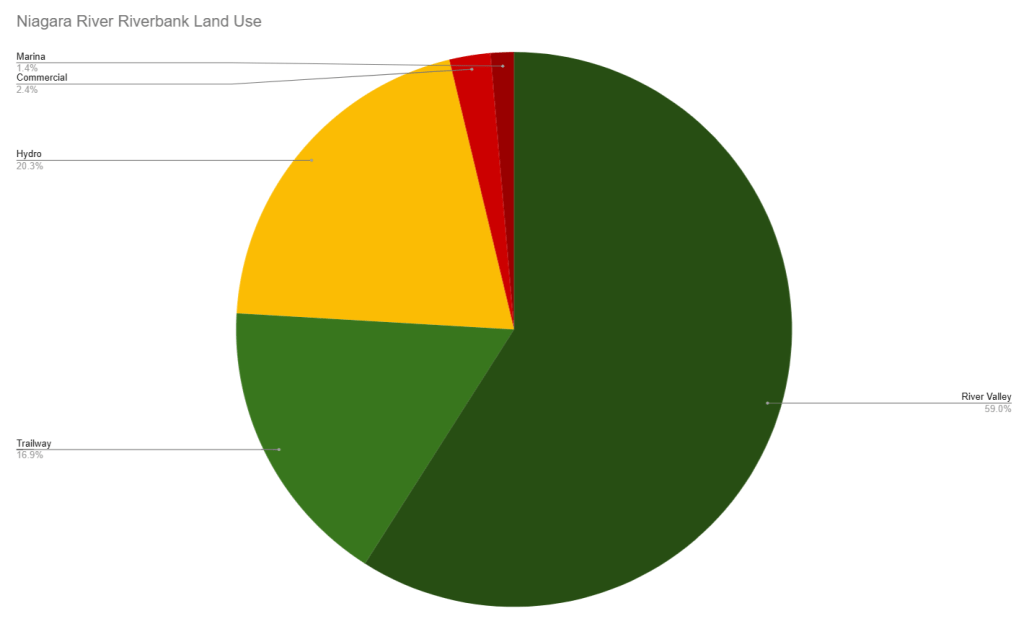

Niagara River

The Horseshoe Falls of the Niagara River are the centrepiece of the region’s tourism, but it would be an injustice to look at the urban Canadian portions of it upstream and downstream of the falls. The river has a long history of hydroelectric power, but is largely still defined by its natural beauty, and attracting tourists has largely driven the open access that’s enjoyed today.

Over three quarters of the Canadian side is publicly open and accessible, although that’s often counting the trails and promenades on the tableland, and ignoring that some bottom sections of the gorge are not open to public access. Another fifth of the bank is restricted by hydroelectric infrastructure, much of which is along an access road south of the Sir Adam Beck Generation Stations, but smaller portions exist upstream of Horseshoe Falls at various tunnel intakes and historic buildings.

Some publicly-restricted portions of the riverbank are driven by paid-access arrangements for tourists, and this is continuing. The Toronto Power Station sits just under a kilometre upstream of Horseshoe Falls, and is a historic site for development of Niagara Falls to generate cheap power for Ontario’s economy. But this is set to be revitalized into a five-star hotel and visitor centre, and the latest renderings suggest its riverside face will be stripped and excluded from free public access.

Notes:

- This mapping is built off of information made available under the Open Government Licence – Ontario v1.0. Some refinement and precision was achieved within the City of Niagara Falls using property parcel data made available under the Open Government Licence – Niagara v2.0.

- All bank length values have been normalized by referencing the centreline extent of the channel. This helps prevent influence from riverbanks that have significant piers, inlets or other wobbles.

- Land on the east bank of the Niagara River was not included as it is across the international border. A comparison would be interjurisdictional apples vs. oranges.

Walks

This project is informed by walking and observing conditions on the ground.

Open Data

This dataset is available in multiple formats through the Open Data Portal